The Origins of Coffee and Ethiopian Traditions

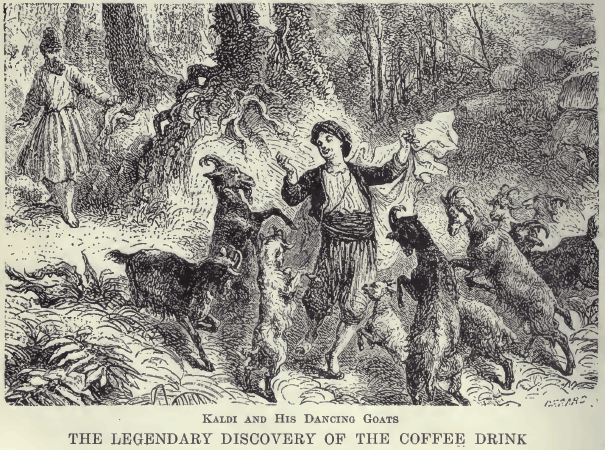

When we hear about the origins of coffee we often hear about goat herders on long journeys from Ethiopia to Yemen, discovering the energy-boosting qualities of the coffee cherry by accident. Although this is true, coffee’s journey from Ethiopia to worldwide commercial production is a complex one that spans across multiple empires, colonialism and the Trans-Atlantic slave trade.

Despite outside influences, Ethiopia remained faithful to its longstanding love affair with drinking coffee. As far back as the 10th century, Oromo warriors were believed to have rolled balls of ripe berries in animal fat and carried them on journeys as rations. This social reliance and significance has never wavered throughout history. European explorers to Africa often documented the importance and appreciation of coffee. David Livingstone and John Kirk, two Scottish explorers, famously accounted stories of African kings and chiefs aiding European expeditions by gifting coffee. It was intended to nourish and energise the souls, fuel tired and often sick bodies, providing the stimulus to cross treacherous waterways and tackle challenging routes. For centuries coffee has woven itself into Ethiopia’s social fabric, so much so it is said that the common phrase that refers to the act of socialising is “buna tetu,” which translates to “drinking coffee” and that one of Ethiopia’s best-known proverbs is “buna dabo naw” or “coffee is our bread.”

The story begins in the Ancient Kingdom of Askum, founded in 150BCE and centred in North Ethiopia. The Empire had direct access to the Upper Nile and Red Sea making it the greatest marketplace and Trade Empire in Africa. Important trade would take place along the Bab-el Mandeb strait, known as the ‘Gates of Tears’ between Ethiopia and Yemen. The expanding Caliphate of the Islamic Empire seized control of the Red Sea and subsequently the coffee trade. During the 14th century they grew tired of trading with Ethiopia and smuggled plants to Yemen to cultivate themselves.

By the 16th century coffee had become an important part of life in the Empire, with an ever-growing economic benefit for its growth and trade, coffee had become in demand and highly lucrative. By now the Ottoman Empire had taken control and built a coffee monopoly that had become a powerful tool which they fiercely protected, they even boiled coffee berries to make them sterile to prevent theft and cultivation elsewhere. The protection was mostly from the looming threat of Colonialism that had begun to rise in the West and eventually led to the downfall of the Ottoman Empires coffee monopoly when the Dutch stole coffee seeds from Yemen in the late 1600s. From Yemen, they were taken to Indonesia, where commercial plantations were set up and the traditional landscape of Ethiopian coffee had gone and Western powers using ideal conquered land and slave labour forces went on to dominate the World coffee trade in the Americas and Asia. Brazil, which was colonised by Portugal, was the leading producer of coffee by the 1830s. It relied on black and indigenous slave labour to grow 30% of the world’s coffee and still to this day dominates world trade and heavily influences the market price with huge amounts of volume harvested each year that can be reserved to be sold at a later date and sold across the board for lower prices than competing origins, all because Brazil has an almost fully automated, machine driven infrastructure for harvesting and processing that decreases the cost of production and need for a large labour force or pickers and sorters.

Fast forward to 2020, Coffee production in Ethiopia is both a labour of love and an important source of income. The crop is embedded deep within the nation’s culture and economy. The industry, directly and indirectly, employed up to 20% of Ethiopia’s 100 million population and around 400,000 hectares area of Ethiopia is under coffee cultivation, of which the vast majority of coffee plants are known to wild varietals and plants. In 2020, Ethiopia was the fifth largest producer of coffee and produced an approximate 400,000 tonnes of green coffee, of which almost 50% was consumed domestically.

There is a reason why so much coffee is kept within the country and not exported for profit around the world. One, its taste and aroma are unique and exquisite, the other is Ethiopians passion and devotion to roasting, preparing and drinking the coffee socially. In western culture you may prepare your coffee by pressing a button, or pushing a plunger, or if you’re really into your brewing you may patiently wait 3 minutes for gravity to work its magic. However in Ethiopia in order to traditionally enjoy coffee with friends and family you may need a spare 45 minutes. The coffee ritual undertaken in Ethiopia is a time-honoured tradition that cannot be rushed. The green beans are roasted in a pan over hot coals, pounded with a pestle and mortar, and then brewed in a traditional pot with a narrow spout. The coffee is drunk from small cups without handles – yet another detail that offers no other choice than to sip slowly and patiently, savouring the effort put into the preparation and honouring the cultural traditions of their ancestors.

25% off

your next order

Enjoy the world's best coffee, freshly roasted & delivered to your door. Sign up to our mailing list for a welcome pack and 25% off your next Cafédirect order!

Thanks for

joining our

mailing list

A welcome pack is on its way and you get 25% off your next Cafédirect order!